404

Looks like you’re looking for something that doesn’t exist. Go to HOME and start again or search below

or checkout our Blogs that might help you better.

or checkout our Blogs that might help you better.

Why Should BCom Graduates and Those with 0-2 Years of Experience Pursue the PGP-BAT Course at Edu Pristine

Know More

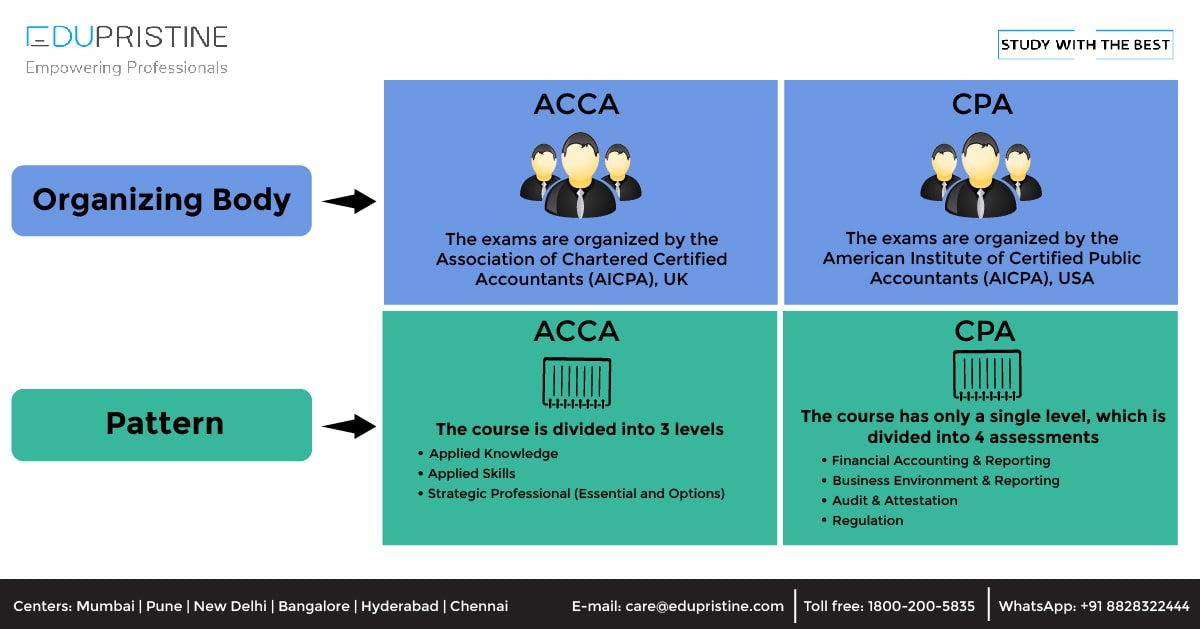

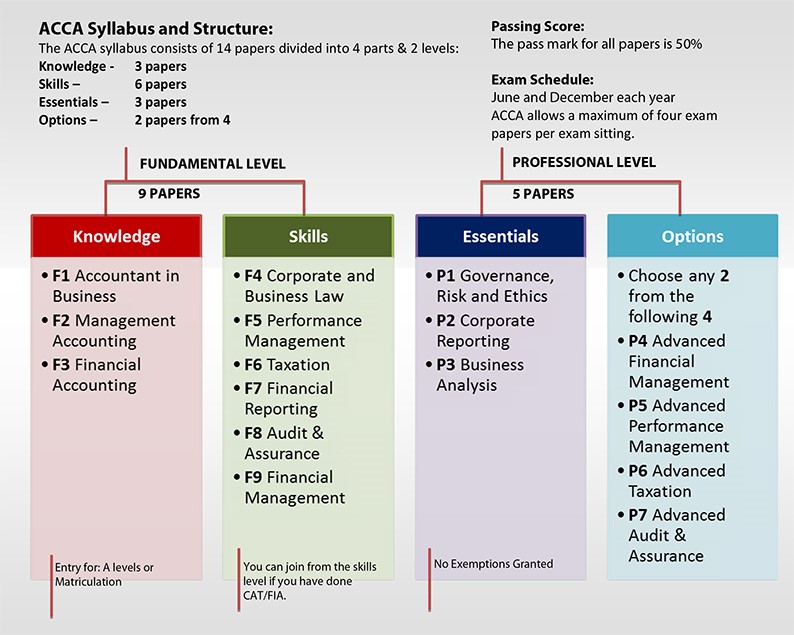

I Desire to Get an ACCA Degree, but the Tuition is too Expensive. Why is the ACCA Course Expensive?

Know More